BBC

BBCIt was a defining moment of the fall of the Syrian regime – rebels freeing inmates from the country’s most notorious prison. A week on, four men speak to the BBC about the elation of their release, and the years of horror that preceded it.

Warning: This article contains descriptions of torture

The prisoners fell silent when they heard the shouting outside their cell door.

A man’s voice called inside: “Is there anyone in there?” But they were too afraid to answer.

Over years, they had learnt that the door opening meant beatings, rapes and other punishments. But on this day, it meant freedom.

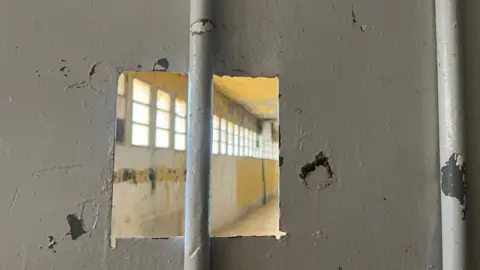

At the shout of “Allahu Akbar”, the men inside the cell peered through a small opening in the centre of the heavy metal door.

There, they saw rebels in the prison’s corridor instead of guards.

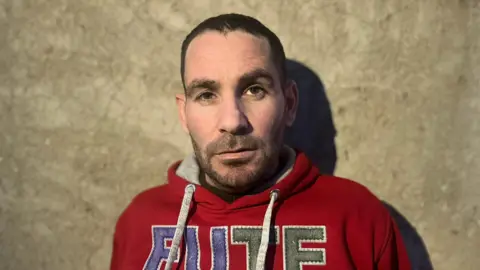

“We said ‘We are here. Free us,’” one of the inmates, 30-year-old Qasem Sobhi Al-Qabalani, recalls.

As the door was shot open, Qasem says he “ran out with bare feet”.

Like other inmates, he kept running and didn’t look back.

“When they came to start liberating us and shouting ‘all go out, all go out’, I ran out of the prison but I was so terrified to look behind me because I thought they’d put me back”, said 31-year-old Adnan Ahmed Ghnem.

They did not yet know that Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad had fled the country and that his government had fallen. But the news soon reached them.

“It was the best day of my life. An unexplainable feeling. Like someone who had just escaped death,” Adnan remembered.

Qasem and Adnan are among four prisoners the BBC has spoken to who were released this week from Saydnaya prison – a facility for political prisoners nicknamed the “human slaughterhouse”.

All gave similar accounts of years of mistreatment and torture at the hands of guards, executions of fellow inmates, corruption by prison officials, and forced confessions.

We were also shown inside the prison by a former inmate who had a similar account, and heard from families of missing people held at Saydnaya who are desperately looking for answers.

We have seen bodies found by rebel fighters in the mortuary of a military hospital, believed to be Saydnaya detainees, that medics say bear signs of torture.

Rights group Amnesty International, whose 2017 report on the prison accuses authorities of murder and torture there, has called for “justice and reparations for crimes under international law in Syria”, including its treatment of political prisoners.

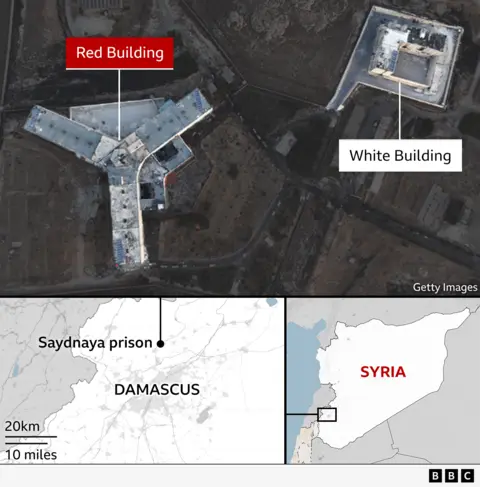

Saydnaya prison, a sprawling complex located atop a hill of barren land and surrounded by barbed wire, was established in the early 1980s and for decades has been used to hold opponents of the Assad family regime.

It has been described as the country’s main political prison since the 2011 uprising, when the Turkey-based Association of Detainees and The Missing in Saydnaya Prison says it effectively became a “death camp”.

The prisoners we spoke to say they were sent to Saydnaya because of real or perceived links with the rebel Free Syrian Army, their opposition to Assad, or simply because they lived in an area known to oppose him.

Some had been accused of kidnapping and killing regime soldiers and convicted of terrorism.

All said they had given confessions under “pressure” and “torture”.

They were given lengthy sentences or sentenced to death. One man said he had been detained at the prison for four years but had not yet been to court.

The men were held in the prison’s main Red Building, for opponents of the regime.

Qasem says he was arrested while passing through a road block in 2016, accused of terrorism with the Free Syrian Army, and sent for short stints at several detention facilities before being transferred to Saydnaya.

“After that door, you are a dead person,” he says softly in an interview at his family home in a town south of Damascus, as relatives gather around sipping coffee and nodding in grim captivation.

“This is where the torture began.”

He recalls being stripped naked and told to pose for a photograph before being beaten for looking at the camera.

He says he was then put onto a chain with other inmates and led, with their faces staring at the ground, to a tiny solitary confinement cell where he and five other men were given uniforms to wear but deprived of food and water for several days.

They were then taken to the prison’s main cells, where the rooms have no beds, a single lightbulb and a small toilet area in the corner.

When we visited the prison this week, we saw blankets, clothes and food strewn on the floors of cells.

Our guide, a former inmate from 2019-2022, walked us through the corridors searching for his cell.

Two of his fingers and a thumb were chopped off at the prison, he says.

Finding scratch marks on a cell wall that he believes he made, he knelt down and began to cry.

About 20 men would sleep in each room, but the inmates tell us it was difficult to get to know each other – they could speak only in hushed voices and knew that guards were always watching and listening.

“Everything was banned. You’re just allowed to eat and drink and sleep and die,” says Qasem.

Punishments at Saydnaya were frequent and brutal.

All of the people we spoke to described being beaten with different implements – metal staffs, cables, electric sticks.

“They would enter the room and start to beat us all over our bodies. I would stay still, watching and waiting for my turn,” Adnan, who was arrested in 2019 on accusations of kidnapping and killing a regime soldier, recalls.

“Every night, we would thank God that we were still alive. Every morning, we would pray to God, please take our souls so we can die in peace.”

Adnan and two of the other newly released inmates said they were sometimes forced to sit with their knees towards their foreheads and a vehicle tyre placed over their bodies with a stick wedged inside so they couldn’t move, before beatings were administered.

Forms of punishment were varied.

Qasem says he was held upside down by two prison officers in a barrel of water until he thought he was going to “choke and die”.

“I saw death with my own eyes,” he says. “They would do this if you woke up in the night, or we spoke in a loud voice, or if we had a problem with any of the other prisoners.”

Two of the prisoners released this week and the former inmate at Saydnaya described witnessing sexual assaults by guards, who they said would anally rape inmates with sticks.

One man said inmates would offer oral sex to the guards in their desperation for more food.

Three described guards jumping on their bodies as part of the abuse.

In a hospital in central Damascus, we were introduced to 43-year-old Imad Jamal, who grimaced in pain at each touch from his mother who was tending to him at his bedside.

Asked to describe his time in Sayndaya, he smiled and responded slowly in English: “No eat. No sleep. Hit. Cane. Fighting. Sick. Everything not normal. Nothing normal. Everything abnormal.”

He said he was detained in 2021 under what he described as a “political arrest” because of the area he was from.

He said his back had been broken when he was made to sit on the ground with his knees against his chest as a guard jumped from a ledge on top of him as a punishment for stealing medication from another inmate to give to a friend.

But for Imad, the hardest thing about life in the prison was the cold. “Even the wall was cold,” he says. “I became a breathing corpse”.

There were few things to look forward to in the prison, but three of the inmates said anything positive was met afterwards with punishment.

“Every time we had a shower, every time we had a visitor, every time we went to court, every time we went out into the sun, every time we left the cell door we would be punished,” says 30-year-old Rakan Mohammed Al Saed, who says he was detained in 2020 on allegations of killing and kidnapping from his former days in the rebel Free Syrian Army but had never faced trial.

He bears his broken teeth, saying they were knocked out when he was hit in the mouth by a guard with a stick.

All of the men we spoke to said they believed people in their cells had been executed.

Guards would come in and call names of people who would be led away and never seen again.

“People wouldn’t be executed in front of us. Every time they would call names at 12am, we knew that those people were going to be killed,” Adnan says.

Others gave similar accounts, explaining there was no way of them knowing what happened to these men.

Qasem’s father and other relatives say the family were made to pay prison officials more than $10,000 to stop him from being executed – at first to be converted to life in prison and then to a 20-year sentence.

Qasem says his treatment by guards improved a bit after this.

But, his dad says, “they refused any amount to let him free”.

Families sent loved ones money for food in the prison but they say corrupt officials would keep much of it and give the inmates only limited rations.

In some of the cells, inmates would pool all of the food together. But it wasn’t enough.

Adnan found the hunger even harder than the beatings. “I would go to sleep and wake up hungry,” he says.

“There was a punishment that we received one month where one day they would pass us a slice of bread, the next day half a slice, until it was a tiny crumb. Then it was nothing. We got no bread.”

Qasem says one day guards covered the face of his cell’s de-facto leader with yoghurt and made others lick it off.

The men said the behaviour of guards was as much about inflicting humiliation as pain.

All described losing significant amounts of weight in the prison because of malnourishment.

“My biggest dream was to eat and be full,” Qasem says.

His family paid officers bribes for visitation rights. He would sometimes be brought down on a wheelchair because he was too weak to walk, his father says.

Diseases were rife and the inmates had no way of stopping them from spreading.

Two of the men we spoke to who were released on Sunday say they had contracted tuberculosis in Sayndaya – one said medication was frequently withheld as a form of punishment.

But Adnan says the “diseases from fear” were even worse than the physical ones.

At a hospital in Damascus this week, an official said brief medical checks of the detainees that were sent there had found “mainly psychological problems”.

These accounts paint a picture of a place with no hope, only pain.

The prisoners spent much of their time in silence with no access to the outside world, so it is no surprise that they say they knew nothing of the rebel Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s (HTS) rapid advance in Syria until they were broken free that morning.

Qasem said they could hear what sounded like a helicopter taking off from the hospital grounds before the men’s shouts in the corridors. But in the windowless cell they couldn’t be sure.

Then the doors openened, and the freed inmates began running as fast as they could.

“We ran out of the prison. We ran from fear too,” Rakan says, his thoughts on his young children and wife.

At one point in the chaos, he says, “I was hit by a car. But I didn’t mind. I got up and carried on running.”

He says he will never go back to Saydnaya again.

Adnan, too, says he couldn’t look back at the prison, as he ran crying towards Damascus.

“I just kept going. I can’t describe it. I just headed for Damascus. People were taking us from the road in their cars.”

He now fears each night when he goes to sleep that he will wake in the prison, and find it was all a dream.

Qasem ran to a town called Tal Mneen. It was there that a woman who provided the freed prisoners with food, money and clothing told them: “Assad has fallen”.

He was brought to his hometown where celebratory gunfire rang out and his tearful family embraced him.

“It’s like I am born again. I can’t describe it to you,” he says.

Additional reporting by Nihad Al-Salem

Leave a Reply