Reuters

ReutersThe prospect of a shy politician is somewhat hard to imagine. Unless that politician is Manmohan Singh.

Since the death of the former Indian prime minister on Thursday, much has been said about the “kind and soft-spoken politician” who changed the course of Indian history and impacted the lives of millions.

His state funeral is being held on Saturday and India’s government has announced an official mourning period of seven days.

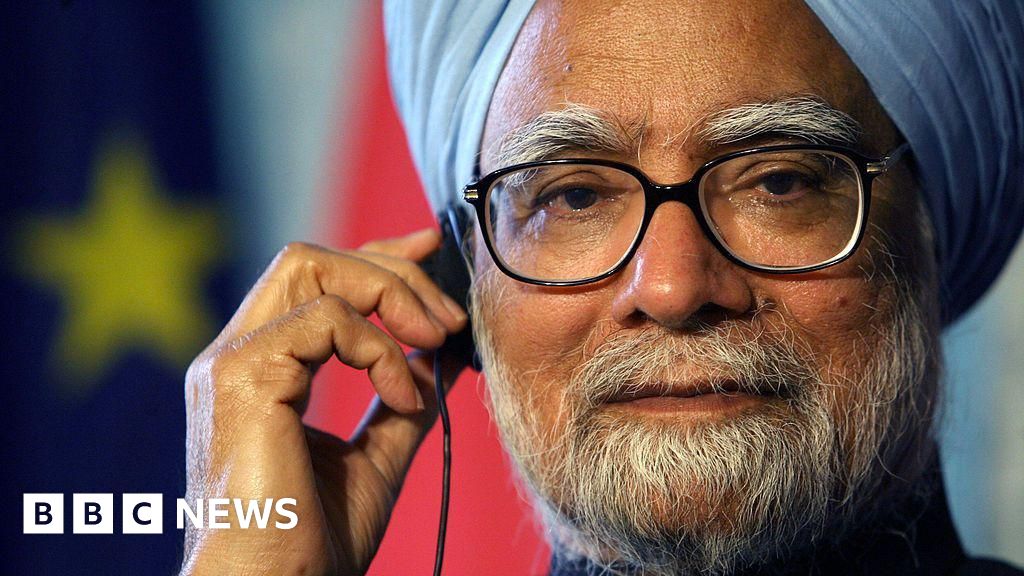

Despite an illustrious career – he was governor of India’s central bank and federal finance minister before becoming a two-term prime minister – Singh never came across as a big-stage politician, lacking the public swagger of many of his peers.

Though he gave interviews and held news conferences, especially in his first term as prime minister, he chose to stay quiet even when his government was mired in scandals or when his cabinet ministers faced corruption allegations.

His gentlemanly ways were both deplored and adored in equal measure.

Reuters

ReutersHis admirers said he was careful not to pick unnecessary battles or make lofty promises and that he focused on results – perhaps best exemplified by the pro-market reforms he ushered in as finance minister which opened India’s economy to the world.

“I don’t think anyone in India believes that Manmohan Singh can do something wrong or corrupt,” his former colleague in the Congress party, Kapil Sibal, once said,. “He was extremely cautious, and he always wanted to be on the right side of the law.”

His opponents, on the other hand, mocked him, saying he exhibited a kind of fuzziness unsuitable for a politician, let alone the premier of a country of more than one billion people. His voice – husky and breathless, almost like a tired whisper – often became the butt of jokes.

But the same voice was also endearing to many who found him relatable in a world of politics where high-pitched and high-octane speeches were the norm.

Singh’s image as a media-shy, unassuming, introverted politician never left him, even when his contemporaries, including his own party members, went through dramatic cycles of reinvention.

Yet, it was the dignity with which he manoeuvred each situation – even the difficult ones – that made him so memorable.

Born to a poor family in what is now Pakistan, Singh was India’s first Sikh prime minister. His personal story – of a Cambridge and Oxford-educated economist who overcame insurmountable odds to rise up the ranks – coupled with his image of an honest and thoughtful leader, had already made him a hero to India’s middle classes.

But in 2005, he surprised everyone when he made a public apology in parliament for the 1984 riots in which around 3,000 Sikhs were killed.

The riots, in which several Congress party members were accused, broke out after the assassination of then-prime minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. One of them later said they shot the Congress politician to avenge a military action she had ordered against separatists hiding in Sikhism’s holiest temple in northern India’s Amritsar.

It was a bold move – no other prime minister, including from the Congress party, had gone so far as to offer an apology. But it provided a healing touch to the Sikh community and politicians across party lines respected him for the courageous act.

Reuters

ReutersA few years later, in 2008, Singh’s understated style of leadership received more praise after he signed a landmark deal with the US that ended India’s decades-long nuclear isolation, allowing India access to nuclear technology and fuel for the first time since it held tests in 1974.

The deal was massively criticised by opposition leaders and Singh’s own allies, who feared it would compromise India’s foreign policy. Singh, however, managed to salvage both his government and the deal.

The period 2008-2009 also witnessed global financial turmoil but Singh’s policies were credited for shielding India from it.

In 2009, he led his party to a resounding victory and returned as the PM for a second term, cementing his image of a benevolent leader, or rather, the exciting idea that leaders could be benevolent.

For many, he had become virtue personified, the “reluctant prime minister” who stayed clear of the spotlight and refused to make any dramatic gestures, but was also not afraid of taking bold decisions for the sake of his country’s future.

Then, things began to unravel.

A string of corruption allegations – first around the hosting of the Commonwealth Games, then the illegal allocation of coal fields – plagued the Congress party and Singh’s government. Some of these corruption allegations were later found to be untrue or exaggerated. Some cases from the period are still pending in courts.

But Singh had already begun to feel some pressure. During his tenure, he made several attempts at reconciliation with India’s arch rival neighbour Pakistan, hoping for a thaw in the decades-old frosty relations.

The approach was sharply questioned in 2008 when a terror attack led by a Pakistan-based terror group killed 171 people in Mumbai city.

The 60-hour siege, one of the bloodiest in the country’s history, opened a chasm of allegations, as the opposition blamed the government’s “soft stance” on terrorism for the tragedy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the coming years, other decisions Singh made badly backfired.

In 2011, an anti-corruption movement led by social activist Anna Hazare shook up Singh’s government. The frail 72-year-old became an icon for the middle classes, as he demanded stringent anti-corruption laws in the country.

As a middle-class hero himself, Singh was expected to deal with Hazare’s demands more perceptively. Instead, the prime minister tried to quash the movement, allowing the police to arrest Hazare and disband his demonstration.

The move stoked a wave of public and media hostility against him. Those who once admired his understated style wondered if they had misjudged the politician and began to see his quiet ways through a less generous lens.

The feeling was heightened the next year when Singh refused to comment on the horrific gang rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi for more than a week.

To make things worse, India’s economic growth was slowing. Corruption grew and jobs shrank, sparking waves of public anger. And Singh’s unassuming personality, which once made his every move seem like a revelation, was labelled as showing complacency, diffidence and even arrogance by some.

Yet, Singh never tried to defend or explain himself and faced the criticism quietly.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat was until 2014. At a rare news conference, he announced that he would not seek a third term in office.

But he also tried to set the record straight. “I honestly believe that history will judge me more kindly than the contemporary media, or for that matter, the opposition parties in parliament did, ” he said, after listing some of the biggest accomplishments of his tenure.

He was right.

As it turned out, neither the Congress, nor Singh, could entirely recover from the damage as they lost the general elections to the BJP. But despite the many hurdles, Singh’s image as a kind and discerning leader stayed with him.

Throughout his prime ministerial stint and despite a second term plagued by controversies, he maintained an aura of personal dignity and integrity.

His policies were seen to centre around the middle class and the poor – he approved manifold increase in salaries of central employees, kept inflation in check and introduced landmark schemes on educations and jobs.

It may not have been enough to elevate him from the quandaries of politics or shield him from some of the failures of his career.

But there was more to his shyness; he was a leader of steely resolve.

Leave a Reply