EPA

EPASouth Korea’s opposition lawmakers have begun impeachment proceedings against President Yoon Suk Yeol over his failed attempt to impose martial law.

The country woke up to an uncertain reality on Wednesday after a night of unprecedented scenes which saw Yoon unexpectedly impose martial law, 190 lawmakers gather to vote it down, and a sudden reversal of the decision around six hours later.

After introducing the impeachment motion, South Korea’s main opposition Democratic Party condemned Yoon’s initial martial law declaration as “insurrectionary behaviour”.

Parliament will have to vote on whether to impeach Yoon by Saturday.

“We can no longer allow democracy to collapse. The lives and safety of the people must be protected,” said Kim Yong-jin, a member of the Democratic party’s central committee.

The Party also said it wants to charge Yoon with “crimes of rebellion”.

It named Minister Kim Yong-hyun and Interior Minister Lee Sang-min as “key participants” of the martial law declaration, saying it also wanted them charged alongside Yoon.

Schools, banks and government offices in Seoul were operating as usual on Wednesday, but protests continued throughout the city demanding the president resign.

“Arrest Yoon Suk-yeol,” some angry citizens chanted as they filled the streets.

South Korea’s largest labour group, the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, vowed to go on indefinite strike until the president steps down.

Reuters

ReutersOn Wednesday, the country’s defence minister Kim Yong-hyun tendered his resignation and said he would take full responsibility for the martial law. He apologised to the public for spreading confusion and causing distress, the ministry said in a statement.

Yoon’s senior aides, including chief of staff Chung Jin-suk and national security adviser Shin Won-sik, also tendered their resignations.

Whether their resignations will be accepted by Yoon is unclear.

The reversal of the shock order early on Wednesday came after dramatic scenes overnight.

Hundreds of troops stormed the parliament after Yoon declared martial law, as military helicopters circled the site.

Some opposition lawmakers broke barricades and climb fences to get to the voting chamber. Woo Won-Shik, the speaker of the National Assembly, told BBC Korea he rushed to parliament thinking “we must protect democracy” and scaled the fence.

Eventually, 190 lawmakers evaded police lines and forced themselves inside to vote down the order.

Thousands of protesters also arrived at the gates of the National Assembly. One woman was captured on video grabbing a soldier’s gun.

“I was scared at first…but seeing such confrontation, I thought, ‘I can’t stay silent’,” Democratic Party spokeswoman Ahn Gwi-ryeong told the BBC.

Yoon’s second announcement – that he was reversing his earlier order – was met with cheers from protesters outside parliament.

Yoon, who won office by the slimmest margin in Korean history and whose approval ratings have hit a record low, said he declared martial law because he was worried about North Korean communist forces taking power in the country.

The presidential office has defended the initial decision as “strictly within [the country’s] constitutional framework”. It said on Wednesday that the announcement was timed to “minimise damage” to the economy and people’s lives.

South Korea’s allies had expressed alarm at the events, with US Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell sharing “grave concern”.

The US and Nato chief Mark Rutte welcomed the rescinded order on Wednesday. Rutte said it showed a commitment to the rule of law and affirmed the alliance’s “iron-clad” relationship with South Korea.

How do impeachments work in South Korea?

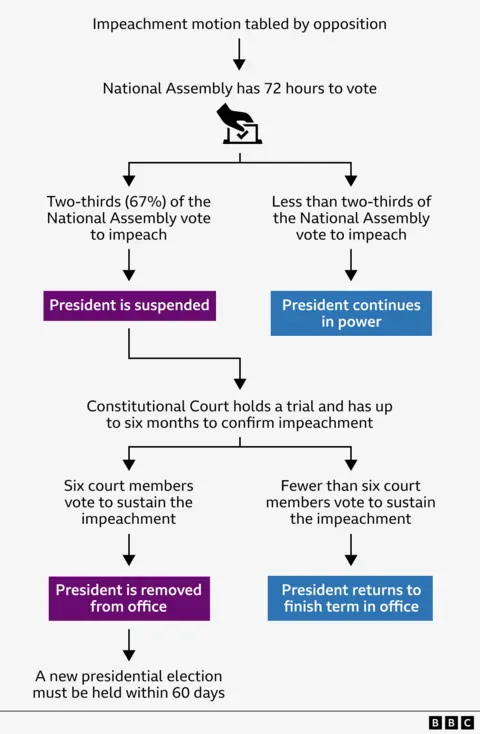

Once an impeachment bill is proposed, two-thirds of South Korea’s 300-member National Assembly must vote to impeach – that translates to at least 200 votes. The vote must take place within 72 hours.

Once the impeachment is approved, the president will immediately be suspended from office, while the prime minister becomes acting president.

A trial will then be held before the Constitutional Court, a nine-member council that oversees South Korea’s branches of government.

If six of the court’s members vote to sustain the impeachment, the president will be removed from office.

Have other South Korean presidents been impeached?

EPA

EPAIn 2016, then-President Park Guen-hye was impeached after she was charged with bribery, abusing state power and leaking state secrets.

In 2004, another South Korean president, Roh Moo-hyun, was impeached and suspended for two months. The Constitutional Court later restored him to office.

If Yoon resigns or is impeached, the government will have to hold an election within 60 days for the country to vote for its new leader, who will start a fresh five-year term.

South Korea’s history with martial law

Under South Korea’s constitution, the president has the authority to declare martial law during war, armed conflict, or other national emergencies.

The last time martial law was declared in the country was in 1979, when the country’s long-time military dictator Park Chung-hee was assassinated in a coup.

A group of military leaders, led by General Chun Doo-hwan, declared martial law in 1980, banning political activities and arresting dissidents.

Hundreds of people died amid a crackdown on protesters before martial law was lifted in 1981.

Martial law has not been invoked since South Korea became a parliamentary democracy in 1987.

Yoon pulled the trigger on Tuesday, saying he was trying to save the country from “anti-state forces”.

But some analysts have described the move as his bid to thwart political opposition.

Yoon has been a lame duck president since the opposition won a landslide in the country’s general election in April this year – his government has not been able to pass the laws it wanted and has been reduced instead to vetoing bills the opposition has proposed.

The president’s approval ratings have hit record lows of 17% this year, as he and his wife Kim Keon-hee have been mired in a spate of scandals.

Additional reporting by Woongbee Lee in Seoul and Frances Mao and Mallory Moench in London

Leave a Reply